©2025 Hello I’m Dead, Inc. All rights reserved.

Contact support@helloimdead.com

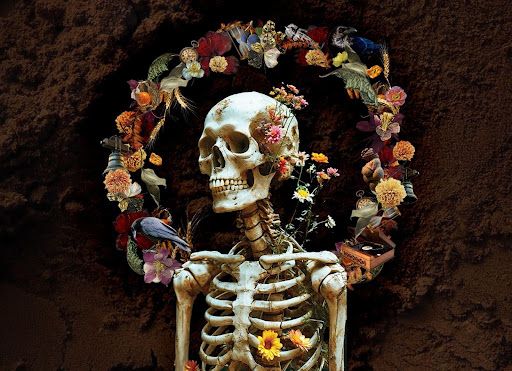

From Mexico’s Día de los Muertos, where families picnic beside graves to commune with ancestors, to Japan’s Obon festival, a midsummer lantern-lit homecoming for the spirits of the departed, death festivals have existed around the world for centuries. These traditions are not just about grief, but about joy. They turn mourning into music, loss into dance, and cemeteries into gathering grounds for the living and the dead. In most English-speaking cultures, grief and mourning are often tucked away, reserved as strictly a private matter. Last month, the inaugural Philadelphia Death and Arts Festival (PDAF) challenged “Western” attitudes towards death and reimagined how Americans confront the culture of dying through performance art, community panels, and celebrating the long ignored.

In recent years, there has been a rise in death and grief festivals in places where residents have identified a need for healthier conversations around dying. In the UK, A Matter of Life and Death Festival started in 2016 and the Good Grief Festival began in 2020. South Australia will have its second Pure Land Death Festival this year. Here in the States, Last Call: An End-of-Life Festival launched in 2022 in St. Louis, Missouri. From May 29th to June 1st, Philadelphia added its voice to this conversation with a multi-day, multidisciplinary gathering hosted at the sprawling Laurel Hill Cemetery. The festival drew artists, death doulas, end-of-life caregivers, and curious attendees into an immersive exploration of what it means to die and live with intention. PDAF’s steering committee also took great care in curating experiences that were cognizant of unjust social hierarchies.

“There are some intense societal structures that shape the way we die that are dehumanizing. These structures don’t center the person who is dying, don’t center their loved ones, don’t center their community of care. [They are] often pushed to outsource that care to professionals [whose] expertise is embedded in a culture that is profit-driven, racist, sexist, and anti-poor,” explains PDAF’s creator, Annie Wilson, who is a Philly-based choreographer, performer, and death doula. When describing how the festival came to be, she recounted conversations with other death workers that believed that “the culture of dying is so dysfunctional” and the community had to “do something to shape, shift, transform” that culture.

Because of Wilson’s decades-long background in performing arts, she knew artists would answer the call to change. “That’s exactly what artists do,” Wilson said, “We examine a big societal question and we ask deep questions about it with the intention of transforming and shifting that culture. That’s where [PDAF] came from. I wanted to bring these professionals who are experts around death and dying, who are on the frontlines of death and dying, who are interacting with people who are aging, dying, and grieving, and I want to bring them in conversation with artists who are asking deep visionary questions about what the future of dying could look like.”

Two of these artists include Eiko Otake and DonChristian Jones. Though separated by a 37-year age gap, these two are friends and collaborators whose performances (A Body in Laurel Hill and The Politics of Mourning IV, respectively) flowed into each other. Jones describes their work as “a practice and performance study around the following questions: Who is allowed to grieve? How are we allowed to grieve? Why and when are we allowed to?” They respond: “I think that grief and mourning are so culturally specific. The ways in which they are made acceptable in the West, particularly in America, [are that they] have been modified to be psychologically violent. I think some of us are not allowed our own grief processes, particularly marginalized bodies, persons of color, the queer body, indigenous bodies. Our methods and practices of grief are often disavowed.”

Jones chose their performance location to be the Receiving Vault of the cemetery because they found the building in need of care and cleaning. It reminded them of taking care of their father in his last days, washing and bathing him. The memories of their father also informed their piece: in the music they chose, the relics that adorned the setting, and the movement of the dance.

Preceding their work was Otake’s performance, moving among the graves, interacting with the audience. One attendee, Lauren Gloudeman, described the piece as representing “different stages of loss and grief… from denying death by covering up the evidence (represented by covering tombstones with shrouds), to carrying the burden of loss alone, before breaking it up into pieces and putting [it] into the hands of those around you… Unexpected interactions with the audience dared us to move closer at times, locking eyes with the artist, and more distant at others, avoiding a certain feeling of responsibility.”

“Art is important,” says Otake, “If we don’t have art, we go into a complete depression. There is a certain grace when we see something that is striking; we are finding our own humanity. We need that medicine. Even when the piece is very dark, being moved by artwork is infinitely a positive experience. I think it is what we need.”

The Philadelphia Death and Arts Festival wasn’t merely a gathering in a cemetery, it was a collective act of reclamation. It invited us not only to confront the realities of death, but to reimagine the systems, rituals, and conversations that shape how we confront the end of life. The festival offered an alternative to silence and erasure. It framed death as an opportunity to deepen our relationships with art, with memory, and with one another. In a society that often seeks to sterilize or monetize death, this festival carved out space for the transformative.

As more places around the world begin to hold festivals of mourning and meaning, PDAF joins a growing movement of people who are no longer content to let grief go unnamed. It showed that the act of dying, like the act of living, deserves artistry, attention, and care. In the words of Otake, “We need that medicine.” May we continue to seek it: in art, in ritual, and in each other.

Join our community and never miss out on exciting opportunities. Sign up today to unlock a world of valuable content delivered right to your inbox.

Different POVs on embracing death and celebrating life.